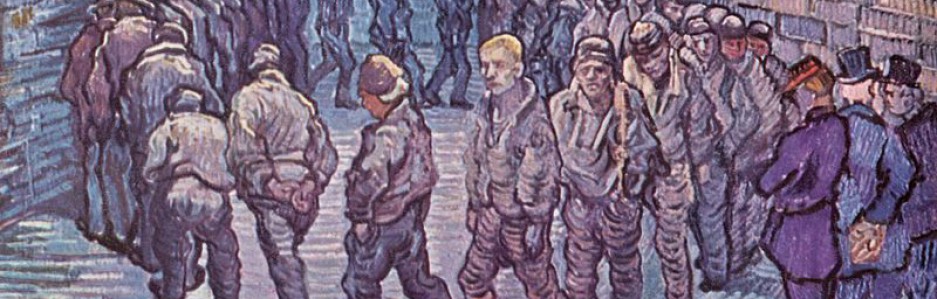

Oscar Wilde experienced life within a Victorian prison himself after being convicted of homosexual offences in 1985. It is interesting to acknowledge that Wilde ‘contributed to mounting public conversation exposing the inhuman treatment of inmates and demanding penal reform as a means of anticolonial mobilization; they ultimately reclaimed the prison as a viable site of communication and aesthetic production’ (1) Although Wilde moved around several prisons, including Newgate, it seems that his time at Reading is perhaps one of the most significant periods of his life in terms of the way it influenced his writing, as ‘The Ballad of Reading Gaol’ is based on both his personal feelings towards prison while also significantlydraws upon the execution of Charles Thomas Wooldridge (executed at age 30) who the poem is written in memoriam of. It is suggested that ‘The Ballad is an indictment of the death penalty and the whole penal system, but it is much more than a protest poem. It is a revelation, and its structure is part of that revelation’ while it is also highlighted that ‘It was first published simply under his prisoner identification number, C.3-3’ (2)

Wilde subtly describes both Wooldridge and questions the penal system throughout the poem.

I never saw a man who looked

With such a wistful eye

Upon that little tent of blue

Which prisoners call the sky,

And at every drifting cloud that went

With sails of silver by. (stanza 3)

This stanza depicts Wilde's personal observation of Wooldridge leading up to his execution, as he had accepted his fate. The phrase 'wistful eye' insinuates the sense that Wooldridge was noticeably nostalgic and perhaps more calm than some prisoners may have been in his situation. Wilde uses the scenic, pleasant imagery of a 'drifting cloud' to reinforce these thoughts, ultimately shifting the focus from Wooldridge's crime itself to the sentimental value of human life. Perhaps one of the most striking sections of the poem is the stanza: I walked, with other souls in pain, Within another ring, And was wondering if the man had done A great or little thing, When a voice behind me whispered low, 'THAT FELLOW'S GOT TO SWING.' This appears to be Wilde's direct approach of challenging the penal system and arguably the death penalty. The spiritual language such as 'other souls' similarly evokes an emotional reaction from readers, reminding them that prisoners should not be dehumanised despite their crimes. Wilde questions whether Wooldridge is guilty or not, yet is reminded that the execution will take place regardless of his thoughts. The use of 'whispered low' creates the sense of an echoing voice, perhaps reflecting the continuation of the penal system process, which does not prioritise individual emotions over laws. The phrase 'that fellows got to swing' sounds shockingly casual in this context, yet this may be for dramatic effect, as creating this juxtaposition with the rest of the language used highlights again to us that the execution is simply a legal process that overlooks the value of human life.

Cited: A. Jarrin, C (2008) 'You Have the Right to Refuse Silence: Oscar Wilde's Prison Letters and Tom Clarke's Glimpses of an Irish Felon's Prison Life' p.85-87 Rumens, C (2009) 'Poem of the Week: The Ballad of Reading Gaol',The Guardian

Wilde, O (1898) 'The Ballad of Reading Gaol'